< Back To Page 1

Much of the paranoia that cursed Sam later in his career was born at this time, and would immediately put him at odds with

prospective studios and producers – even those who were truly supportive. Such head-butting tactics kept smaller, more personal

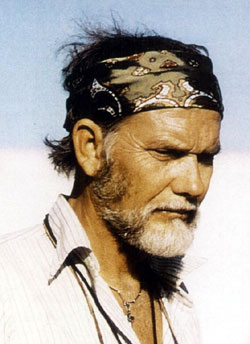

films like Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) from receiving proper distribution. This dirt-smeared paean to the lonesome

loser, starring long-standing Peckinpah stock company member, Warren Oates, may be the most personal of all Sam’s pictures. The

role of Bennie, a piano player in a seedy Mexican bar, who sees salvation through the bounty offered on the head of a small-time

lothario, is tailor-make for Oates in a rare lead role. To fully embrace the paranoia of the character, Oates decided to play the

character as…Sam Peckinpah—something that gave everyone who knew Sam quite a kick when they saw the film. Fuelled by an

ever-growing drug habit, Sam’s paranoia made him almost impossible to work with. He would routinely plant bugs in the hotel

rooms of friends, business associates and even his own wife. The films made in this period reflected this state of mind,

loser, starring long-standing Peckinpah stock company member, Warren Oates, may be the most personal of all Sam’s pictures. The

role of Bennie, a piano player in a seedy Mexican bar, who sees salvation through the bounty offered on the head of a small-time

lothario, is tailor-make for Oates in a rare lead role. To fully embrace the paranoia of the character, Oates decided to play the

character as…Sam Peckinpah—something that gave everyone who knew Sam quite a kick when they saw the film. Fuelled by an

ever-growing drug habit, Sam’s paranoia made him almost impossible to work with. He would routinely plant bugs in the hotel

rooms of friends, business associates and even his own wife. The films made in this period reflected this state of mind,

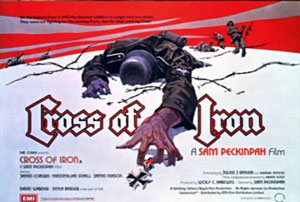

with only Cross of Iron (1976) showing the director in recognizable form. The story of a German platoon lost behind enemy

lines during the horrific retreat from Russia was meant to stand in stark contrast to the heroic WWII films that most of

us had grown up with. Focusing on a preening, Prussian officer (Maximilian Schell, in a beautiful performance) willing to

sacrifice the lives of his men in a quest for Germany’s highest military award, the film deserves credit for being one of the

finest films to show the war from the German perspective, and to cast the soldiers in a sympathetic light (Das Boot would

not come for several years). Financed with German money and shot in remote, eastern European locations, the film was a tough

slog even by Peckinpah standards. A strong cast headed-up by old friend James Coburn helps to make the difficult subject matter

more palatable, but the abortive ending belies more production trouble, as the money ran out and the producers disappeared

near the end of filming. The film received a spotty theatrical release and rarely shows up on television

with only Cross of Iron (1976) showing the director in recognizable form. The story of a German platoon lost behind enemy

lines during the horrific retreat from Russia was meant to stand in stark contrast to the heroic WWII films that most of

us had grown up with. Focusing on a preening, Prussian officer (Maximilian Schell, in a beautiful performance) willing to

sacrifice the lives of his men in a quest for Germany’s highest military award, the film deserves credit for being one of the

finest films to show the war from the German perspective, and to cast the soldiers in a sympathetic light (Das Boot would

not come for several years). Financed with German money and shot in remote, eastern European locations, the film was a tough

slog even by Peckinpah standards. A strong cast headed-up by old friend James Coburn helps to make the difficult subject matter

more palatable, but the abortive ending belies more production trouble, as the money ran out and the producers disappeared

near the end of filming. The film received a spotty theatrical release and rarely shows up on television

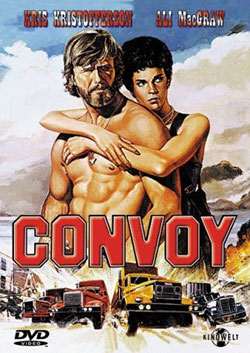

1978 became the nadir of Sam’s professional life; it would mark the last time he would direct a film for 5 years, and demonstrate

for the industry the havoc that a decade of abuse of the body and mind could produce. The picture in question, Convoy, is

quite simply, a sad catastrophe of a film. This time it was the studio and the editors who came to the rescue, managing to

assemble the ill-fitting odds and ends into something resembling a motion picture. Based loosely (as if there were a way to

form a faithful adaptation) on C.W. McCall’s eponymous trucker anthem, Convoy features Kris Kristofferson as “Rubber Duck”

and Ernest Borgnine as Sheriff Lyle Wallace in the type of lonesome-highway cat & mouse game that’s best left to the realm

of song lyrics and drunken, late night pronouncements made over a CB radio. The “convoy” of the title comes in the form of a

mile-long line of 18-wheelers formed in support of the Duck. All who might be tempted to dismiss the talents of Hal Needham

would do well to compare this outrageously bloated and self-important mess with the Smokey & The Bandit movies that were

being made at almost exactly the same time (one might wonder how the goods of a nation were transported with seemingly every

available truck pressed into service for these films). Needham’s movies are a beer-spillin’ hoot that never comes remotely close

to taking themselves seriously. With Convoy, we wait patiently for the Sam Peckinpah movie that never starts. Instead we’re

treated to an orgy of second-unit-shot vehicular mayhem, many with Sam’s signature slow motion effect that is cheapened beyond

the point of parody. The cruelest irony might have been that Convoy, the only Sam Peckinpah movie that could be fairly described as “embarrassing”, would go on to be the biggest hit of his career.

1978 became the nadir of Sam’s professional life; it would mark the last time he would direct a film for 5 years, and demonstrate

for the industry the havoc that a decade of abuse of the body and mind could produce. The picture in question, Convoy, is

quite simply, a sad catastrophe of a film. This time it was the studio and the editors who came to the rescue, managing to

assemble the ill-fitting odds and ends into something resembling a motion picture. Based loosely (as if there were a way to

form a faithful adaptation) on C.W. McCall’s eponymous trucker anthem, Convoy features Kris Kristofferson as “Rubber Duck”

and Ernest Borgnine as Sheriff Lyle Wallace in the type of lonesome-highway cat & mouse game that’s best left to the realm

of song lyrics and drunken, late night pronouncements made over a CB radio. The “convoy” of the title comes in the form of a

mile-long line of 18-wheelers formed in support of the Duck. All who might be tempted to dismiss the talents of Hal Needham

would do well to compare this outrageously bloated and self-important mess with the Smokey & The Bandit movies that were

being made at almost exactly the same time (one might wonder how the goods of a nation were transported with seemingly every

available truck pressed into service for these films). Needham’s movies are a beer-spillin’ hoot that never comes remotely close

to taking themselves seriously. With Convoy, we wait patiently for the Sam Peckinpah movie that never starts. Instead we’re

treated to an orgy of second-unit-shot vehicular mayhem, many with Sam’s signature slow motion effect that is cheapened beyond

the point of parody. The cruelest irony might have been that Convoy, the only Sam Peckinpah movie that could be fairly described as “embarrassing”, would go on to be the biggest hit of his career.

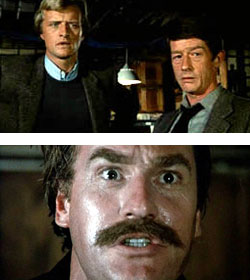

Unfortunately, this success did not lead to securing the artistic freedom to make more deeply felt, personal films. Instead,

stories of a nearly comatose director would scare away even the least sensible producer. After an ignominious stint on 1982’s

Jinxed covering for old pal Don Siegel who had fallen ill, Sam began work the next year on his final film, an adaptation of

Robert Ludlum’s bestseller The Osterman Weekend (1983). Peckinpah’s name attracted top-line talent (Burt Lancaster and John Hurt),

rising stars (Rutger Hauer) and some actors whose careers were so deep in the crapper that even Sam might have had a giggle at their

expense (Dennis Hopper). In recent years, the producers of the Jason Bourne series of films have finally figured out how to

make a successful adaptation of a Ludlum book—toss out most of the over-plotted story, which seems to have been designed for

little else than to ease airline passengers to sleep on long flights. Alan Sharpe’s script attempts to tackle the story—a

Unfortunately, this success did not lead to securing the artistic freedom to make more deeply felt, personal films. Instead,

stories of a nearly comatose director would scare away even the least sensible producer. After an ignominious stint on 1982’s

Jinxed covering for old pal Don Siegel who had fallen ill, Sam began work the next year on his final film, an adaptation of

Robert Ludlum’s bestseller The Osterman Weekend (1983). Peckinpah’s name attracted top-line talent (Burt Lancaster and John Hurt),

rising stars (Rutger Hauer) and some actors whose careers were so deep in the crapper that even Sam might have had a giggle at their

expense (Dennis Hopper). In recent years, the producers of the Jason Bourne series of films have finally figured out how to

make a successful adaptation of a Ludlum book—toss out most of the over-plotted story, which seems to have been designed for

little else than to ease airline passengers to sleep on long flights. Alan Sharpe’s script attempts to tackle the story—a

successful TV reporter is informed that a group of college friends are actually enemy agents, and allows a shadowy government

agency access to his house over a weekend to spy on them during a yearly weekend visit—in its entirety, leaving in the various

double and triple crosses that read like narrative mush in the source book. It was a story uniquely ill-suited to Peckinpah’s

strengths. It is likely that Sam saw the film as his entree back into the mainstream, and to show the world that he could

deliver a project on time and on budget - but the resulting film was a dull, passionless affair with an execrable musical

score; its maudlin jazz synth rhythms date the film to the early 80s quicker than a hundred piano-key neckties.

successful TV reporter is informed that a group of college friends are actually enemy agents, and allows a shadowy government

agency access to his house over a weekend to spy on them during a yearly weekend visit—in its entirety, leaving in the various

double and triple crosses that read like narrative mush in the source book. It was a story uniquely ill-suited to Peckinpah’s

strengths. It is likely that Sam saw the film as his entree back into the mainstream, and to show the world that he could

deliver a project on time and on budget - but the resulting film was a dull, passionless affair with an execrable musical

score; its maudlin jazz synth rhythms date the film to the early 80s quicker than a hundred piano-key neckties.

Sam Peckinpah died a few days after Christmas in 1984, his swan song being a pair of Julian Lennon music videos shot as part

of a documentary that would never be completed. In the ensuing years, many of Sam’s butchered films have been re-assembled as

he had envisioned them. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and The Wild Bunch have been fully restored on home video, with the former

about to receive its DVD debut in January as part of the Warner Bros. Sam Peckinpah box set (along with Ride the High Country and

The Ballad of Cable Hogue.) Columbia has restored as much of Major Dundee as will likely ever be possible. Although it is still not

what Sam had intended, the viewer has a fighting chance to see what might have been. Shortly after Sam’s death, friends and

family got together to celebrate Sam's life. Kris Kristofferson performed "Sam’s Song," summing up the spirit of the man better than any eulogy could have.

of a documentary that would never be completed. In the ensuing years, many of Sam’s butchered films have been re-assembled as

he had envisioned them. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and The Wild Bunch have been fully restored on home video, with the former

about to receive its DVD debut in January as part of the Warner Bros. Sam Peckinpah box set (along with Ride the High Country and

The Ballad of Cable Hogue.) Columbia has restored as much of Major Dundee as will likely ever be possible. Although it is still not

what Sam had intended, the viewer has a fighting chance to see what might have been. Shortly after Sam’s death, friends and

family got together to celebrate Sam's life. Kris Kristofferson performed "Sam’s Song," summing up the spirit of the man better than any eulogy could have.

I said, “Willie old buddy, please tell me again

The reason we keep goin’ on.”

He said, “There’s no harder words to say over a friend

Than they done you so righteously wrong.

They stopped you from singing your song.”

As Sam once prophetically stated, "The end of a picture is always an end of a life."

< Back To Page 1

|