"THE END OF A PICTURE IS ALWAYS AN END OF A LIFE"

The Blood and Guts

of Sam Peckinpah

By Drew Fitzpatrick

With talent forged in the salt mines of network television westerns, Sam Peckinpah quickly made a name for himself as both a

skillful writer and director, on top shows like The Westerner and The Rifleman. This success led rapidly to features, and in

1962 had his first real hit with Ride the High Country, a lean action-drama starring genre favorites Randolph Scott and

Joel McCrea as former friends who find themselves on opposite sides of the law in the waning days of the old west. Peckinpah’s

characters, even though on opposite sides, each stood by their own code of conduct, one to which they held both themselves and

the world around them. They’ll walk head-on into a hale of gunfire rather than compromise their principals, a situation which

in lesser hands often seemed clichéd, but in Sam’s world it was as natural as the sunrise. The picture was a sizeable hit and

Sam found himself a hot property in Hollywood, with several studios courting him for more prestigious productions.

Major Dundee (1965) was initially intended as an expensive road show-style production, but a skittish producer (a veteran of

little more than Giget movies) and studio soon ordered cuts both in budget and scope. The story of reckless union cavalry officer

Dundee (Charlton Heston) who press-gangs a group of Confederate prisoners into invading Mexico, hunting for an Apache raiding

party, was to become a horse-opera version of Moby Dick and a mid-60s metaphor for imperialist expansion. During production,

Columbia Studios began to get cold feet and began drastically scaling back the production. Sam, flush with confidence, continued to

film the story as he saw it, only to get himself locked out of the editing room and have the film cut without him. This would

be the first of many projects that the hot-headed director would have wrenched from him during the crucial editing phase. Letters

of protest to the producer and various studio heads were ignored, with Peckinpah even threatening to remove his name from the

credits (career suicide in those days) Dundee became both a personal and a public failure, and Sam only directed one film

(the television drama Noon Wine) during the next four years. But when a new Sam Peckinpah film finally did open in 1969, it

proved to be far more than merely the unqualified hit that the director desperately needed.

With The Wild Bunch, the new Hollywood permanently uncoupled itself from the traditional western. The subversive genre

explorations of Sergio Leone and his countrymen had been chipping away at the Hollywood-style western for years, and Hollywood

was only able to answer back with pathetically anemic fare like Howard Hawks’ sad career capper, Rio Lobo. Peckinpah’s film was

a savagely violent saga about professional killers fighting on both sides of the law. The heroes of the film are a murderous gang

of outlaws led by William Holden and Ernest Borgnine, and the villains are an even more brutal gang, reluctantly led by former

outlaw Robert Ryan. The unusually accurate tagline on its poster read “A brutal drama of violent men who had outlived their

time,” and the plot (the theft and sale of guns to a Mexican warlord with railroad deputies in hot pursuit) is simplicity itself.

But Peckinpah used this uncomplicated framework to perfectly craft his vision of rugged individuals raging against a world

that doesn’t fit them. It’s almost impossible to understate the influence that The Wild Bunch would have—not just on young filmmakers,

but on the American movie-going public. Although Bonnie & Clyde is widely credited with shattering the taboo of acceptable

on-screen violence 2 years earlier, it was Sam who removed the fashion-magazine gloss, and while still appearing stylized,

the scenes of carnage played out like a gut punch. Sam’s particular style of slow-motion violence set his early films apart

from the pack, but would, a decade down the line, become a technique used by rote rather than by dramatic necessity. Later

pictures such as The Killer Elite (1975) ran the idea into the ground, with slow-motion being used for everything from gun fights

to characters getting into and out of cars. Producers would hire Sam only to have his “style” imprinted in as many scenes as

possible, moving the technique rapidly into the realm of self-parody. Whereas Warren Beatty’s Clyde Barrow was an affable gent

regretfully reduced to gunplay only after provocation, Pike Bishop (Holden) and his men would shoot you dead at the drop of a hat.

Peckinpah acknowledges the ferocity, but his sentiments are clearly with them. Sam related to hard, self-made men throughout his

entire career—men who not only refused to adapt to changing times but would rather die than be swept aside. When Holden ruefully states

that “It’s about time we start lookin’ past our guns,” it’s not a throwaway line, but rather the sad resignation of a man who finds

it impossible to continue living by his own code. In the end, the Bunch decide to fight and die, rather

than take their money and go; and when Peckinpah eulogizes them in the very last shot, superimposing images of the Bunch

having the last laugh, Sam’s feelings regarding living and dying on your own terms become crystal clear: It’s what makes you

someone worth remembering. Sam always saw himself as a like-minded maverick, railing against the injustices of a studio

system that perverted art and attempted to compromise his vision. In the end, massive substance abuse would lead to an

almost complete retreat into self-aggrandizing visions in which it was Sam against the world—alienating friends and supporters

alike until Sam would have no one but himself to blame for his career being in shambles.

With The Wild Bunch, the new Hollywood permanently uncoupled itself from the traditional western. The subversive genre

explorations of Sergio Leone and his countrymen had been chipping away at the Hollywood-style western for years, and Hollywood

was only able to answer back with pathetically anemic fare like Howard Hawks’ sad career capper, Rio Lobo. Peckinpah’s film was

a savagely violent saga about professional killers fighting on both sides of the law. The heroes of the film are a murderous gang

of outlaws led by William Holden and Ernest Borgnine, and the villains are an even more brutal gang, reluctantly led by former

outlaw Robert Ryan. The unusually accurate tagline on its poster read “A brutal drama of violent men who had outlived their

time,” and the plot (the theft and sale of guns to a Mexican warlord with railroad deputies in hot pursuit) is simplicity itself.

But Peckinpah used this uncomplicated framework to perfectly craft his vision of rugged individuals raging against a world

that doesn’t fit them. It’s almost impossible to understate the influence that The Wild Bunch would have—not just on young filmmakers,

but on the American movie-going public. Although Bonnie & Clyde is widely credited with shattering the taboo of acceptable

on-screen violence 2 years earlier, it was Sam who removed the fashion-magazine gloss, and while still appearing stylized,

the scenes of carnage played out like a gut punch. Sam’s particular style of slow-motion violence set his early films apart

from the pack, but would, a decade down the line, become a technique used by rote rather than by dramatic necessity. Later

pictures such as The Killer Elite (1975) ran the idea into the ground, with slow-motion being used for everything from gun fights

to characters getting into and out of cars. Producers would hire Sam only to have his “style” imprinted in as many scenes as

possible, moving the technique rapidly into the realm of self-parody. Whereas Warren Beatty’s Clyde Barrow was an affable gent

regretfully reduced to gunplay only after provocation, Pike Bishop (Holden) and his men would shoot you dead at the drop of a hat.

Peckinpah acknowledges the ferocity, but his sentiments are clearly with them. Sam related to hard, self-made men throughout his

entire career—men who not only refused to adapt to changing times but would rather die than be swept aside. When Holden ruefully states

that “It’s about time we start lookin’ past our guns,” it’s not a throwaway line, but rather the sad resignation of a man who finds

it impossible to continue living by his own code. In the end, the Bunch decide to fight and die, rather

than take their money and go; and when Peckinpah eulogizes them in the very last shot, superimposing images of the Bunch

having the last laugh, Sam’s feelings regarding living and dying on your own terms become crystal clear: It’s what makes you

someone worth remembering. Sam always saw himself as a like-minded maverick, railing against the injustices of a studio

system that perverted art and attempted to compromise his vision. In the end, massive substance abuse would lead to an

almost complete retreat into self-aggrandizing visions in which it was Sam against the world—alienating friends and supporters

alike until Sam would have no one but himself to blame for his career being in shambles.

The Wild Bunch would have an unexpected, adverse effect on Peckinpah’s career, with each subsequent film being the subject of

an unfavorable comparison to his 1969 masterpiece. His best work might indeed have been behind him, but Sam didn’t know it yet.

After 1970’s elegiac The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Sam moved away from the American landscape entirely to film an adaptation of

Gordon Williams’ novel, The Siege at Trencher’s Farm. Straw Dogs premiered in 1971 and quickly became the most controversial

film in Peckinpah’s career. He was vilified by feminists as a misogynist and by liberals as a fascist, and the film remains a lightening

rod for controversy 35 years after its release. Bookish American professor David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) and his young wife

Amy (Susan George) have just taken up residence in the Cornwall district of England. For David, the peace and quiet of the

British countryside will allow him to concentrate on his work and for Amy it means coming home—both to the town in which

she grew up, and to Charlie, the boyfriend that she left behind. Amy’s old flame runs with a rough crowd of unemployed young

toughs who manage to scavenge for work fixing up the farm house that David and Amy have rented. David, lost in work, spurns

Amy, who retaliates by flirting with the workmen. While a few of the locals distract David with a hunting trip, Amy is attacked

and raped by two that stayed behind. Though she doesn’t tell David what happened, he’s smart enough to know that he’s become the

butt of the toughs' jokes (they abandoned him in the middle of a field), and when the hulking village idiot, Niles (an early

performance from the great David Warner) accidentally kills a local girl, David shelters him from a lynch mob—and defends

his home with a stunning display of barbarity.

The Wild Bunch would have an unexpected, adverse effect on Peckinpah’s career, with each subsequent film being the subject of

an unfavorable comparison to his 1969 masterpiece. His best work might indeed have been behind him, but Sam didn’t know it yet.

After 1970’s elegiac The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Sam moved away from the American landscape entirely to film an adaptation of

Gordon Williams’ novel, The Siege at Trencher’s Farm. Straw Dogs premiered in 1971 and quickly became the most controversial

film in Peckinpah’s career. He was vilified by feminists as a misogynist and by liberals as a fascist, and the film remains a lightening

rod for controversy 35 years after its release. Bookish American professor David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) and his young wife

Amy (Susan George) have just taken up residence in the Cornwall district of England. For David, the peace and quiet of the

British countryside will allow him to concentrate on his work and for Amy it means coming home—both to the town in which

she grew up, and to Charlie, the boyfriend that she left behind. Amy’s old flame runs with a rough crowd of unemployed young

toughs who manage to scavenge for work fixing up the farm house that David and Amy have rented. David, lost in work, spurns

Amy, who retaliates by flirting with the workmen. While a few of the locals distract David with a hunting trip, Amy is attacked

and raped by two that stayed behind. Though she doesn’t tell David what happened, he’s smart enough to know that he’s become the

butt of the toughs' jokes (they abandoned him in the middle of a field), and when the hulking village idiot, Niles (an early

performance from the great David Warner) accidentally kills a local girl, David shelters him from a lynch mob—and defends

his home with a stunning display of barbarity.

Misreading Straw Dogs has almost become a vocation among both critics and audiences in the decades since its release. Most of

the controversy and confusion centers on the rape scene, occurring just past the halfway mark of the film. What begins as an

attack by Amy’s former boyfriend shockingly turns into a love scene, as Amy rediscovers a passion that she never shared with

David. But the scene takes a second startling turn when another of the local men decides that Charlie ought to “share” his

prize. The ensuing rape is the most brutally violent scene that Sam ever shot, without spilling a drop of blood. The delicate

rhythm of the editing allows us to experience the moment through the eyes of each character, and the result is the most

delicately assembled scene in any of Sam’s work. Many critics went along with the argument that Peckinpah believed that the

rite of passage to true manhood is violence. David is a timid, cuckolded academic; he's an insignificant person until he

finds his backbone. To be certain, Sam seems to have little respect for David—even when his character is in the right, he’s

made to look petty and stubborn. When David finally stands up for himself and refuses to let the drunken mob take (and most

likely kill) Niles, it isn’t a victory. David commits repugnant, violent acts in the defense of his home, but Peckinpah never

celebrates it. In his world, there is no passage to manhood through acts of violence, only the destruction of one’s own

humanity. The oft-quoted exchange between David and Niles at the film’s end sums up Sam’s feelings:

Niles: “I don’t know my way home.”

David: “Neither do I.”

After The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs is Peckinpah’s most perfectly realized film. It’s a shattering, scalding picture, with career-best

performances from Hoffman, but particularly from George, who shows an enormous potential that strangely remained unfulfilled.

A two-picture collaboration with Steve McQueen in 1972 produced Sam’s first true commercial triumph, The Getaway, and a

little-seen mediation on family set in the Texas rodeo circuit, Junior Bonner. The former gave McQueen the hit he badly needed,

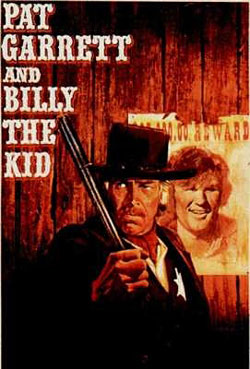

and the latter gave Sam a relatively stress- and controversy-free production. 1973’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid would be Sam’s

final western, his very personal farewell to a genre that he elevated. Starring, respectively, James Coburn and

Kris Kristofferson as the titular characters, it follows the familiar framework of the William Bonnie legend in the form of a

cinematic jazz riff rather than a more covenantal narrative. Garrett and Bonnie had been friends, and share the same respect

for each other that men on opposite sides often do in the Peckinpah universe. Early on, Garrett, a newly minted railroad deputy, and

Bonnie meet at Old Fort Sumner in New Mexico. When Garrett tells the kid that he’s got five days to exit the territory, Bonnie's reply is: “Are they asking

me, or are they telling me?” Garrett's retort carries a certain weight. “I’m asking…but in five days, I’m making you.” The rest, as they say, is history.

A two-picture collaboration with Steve McQueen in 1972 produced Sam’s first true commercial triumph, The Getaway, and a

little-seen mediation on family set in the Texas rodeo circuit, Junior Bonner. The former gave McQueen the hit he badly needed,

and the latter gave Sam a relatively stress- and controversy-free production. 1973’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid would be Sam’s

final western, his very personal farewell to a genre that he elevated. Starring, respectively, James Coburn and

Kris Kristofferson as the titular characters, it follows the familiar framework of the William Bonnie legend in the form of a

cinematic jazz riff rather than a more covenantal narrative. Garrett and Bonnie had been friends, and share the same respect

for each other that men on opposite sides often do in the Peckinpah universe. Early on, Garrett, a newly minted railroad deputy, and

Bonnie meet at Old Fort Sumner in New Mexico. When Garrett tells the kid that he’s got five days to exit the territory, Bonnie's reply is: “Are they asking

me, or are they telling me?” Garrett's retort carries a certain weight. “I’m asking…but in five days, I’m making you.” The rest, as they say, is history.

In terms of plot, there really isn’t much to work with. What energized Peckinpah was the opportunity to create little

character moments, almost like blackout sketches, in which Sam could work out his favorite themes. In the most memorable,

Garrett enlists the aid of local sheriff (Slim Pickens) in tracking down a few of the gang members. All concerned, Garrett, the

sheriff, and the gang members all know each other from “the old days.” The shootout begins as a typical Hollywood western

gunfight, but quickly turns mournful and tragic, taking the lives of almost all concerned. Pickens, whose career as a western

character actor went back nearly 25 years, gets his finest on-screen moment, staggering mortally wounded to a river bank to

spend his last few moments gazing at the face of his wife, to the strains of Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

The expression on his face is a master class in film acting, saying more than 10 pages of dialogue could ever have. Many

fabulous character actors get similar moments here, Jack Elam, R.G. Armstrong, Chill Wills, Barry Sullivan, and even Jason Robards

contribute glorious grace notes to the proceedings. Dylan composed the entire musical score for the film, in addition to taking

a small role. Consisting of both individual songs and incidental music, the score has some of Dylan’s finest work of

the 70s. Instead of severely dating the film (as most rock scores do) Dylan’s music gives it a timeless quality, setting it apart

from any other American western. The film's episodic structure eventually becomes harmful to the pacing, and potential viewers

without a pre-existing love for the performers or director might be well advised to begin their Peckinpah experience elsewhere.

During James Aubrey’s reign of terror as MGM’s president in the early 70s, many top directors saw their immensely personal

projects hacked to pieces—to both shorten and, at least in the mind of Aubrey, “uncomplicate” them. Blake Edwards saw two ambitious films, The Carey Treatment

and The Wild Rovers, fall victim to Aubrey’s editing cleaver—but it was Sam’s turn with Garrett, with almost 20 minutes of

footage carelessly cut out. Gone was the carefully crafted opening, cutting between Garrett’s murder in 1901 with his arrival

at Fort Sumner in 1881, along with many other scenes deemed “unnecessary” to the story. At the time of the merciless editing, rather than pleading his case calmly, Sam

exploded in every direction, blaming close friends for betraying him—even at one point stealing away the reels of his

edit from the cutting room into a waiting pickup truck. The story may be apocryphal, but when Sam’s cut turned up on

Los Angeles’ Z-Channel, it came directly from Sam’s hand—from his own “personal archives.”

spend his last few moments gazing at the face of his wife, to the strains of Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

The expression on his face is a master class in film acting, saying more than 10 pages of dialogue could ever have. Many

fabulous character actors get similar moments here, Jack Elam, R.G. Armstrong, Chill Wills, Barry Sullivan, and even Jason Robards

contribute glorious grace notes to the proceedings. Dylan composed the entire musical score for the film, in addition to taking

a small role. Consisting of both individual songs and incidental music, the score has some of Dylan’s finest work of

the 70s. Instead of severely dating the film (as most rock scores do) Dylan’s music gives it a timeless quality, setting it apart

from any other American western. The film's episodic structure eventually becomes harmful to the pacing, and potential viewers

without a pre-existing love for the performers or director might be well advised to begin their Peckinpah experience elsewhere.

During James Aubrey’s reign of terror as MGM’s president in the early 70s, many top directors saw their immensely personal

projects hacked to pieces—to both shorten and, at least in the mind of Aubrey, “uncomplicate” them. Blake Edwards saw two ambitious films, The Carey Treatment

and The Wild Rovers, fall victim to Aubrey’s editing cleaver—but it was Sam’s turn with Garrett, with almost 20 minutes of

footage carelessly cut out. Gone was the carefully crafted opening, cutting between Garrett’s murder in 1901 with his arrival

at Fort Sumner in 1881, along with many other scenes deemed “unnecessary” to the story. At the time of the merciless editing, rather than pleading his case calmly, Sam

exploded in every direction, blaming close friends for betraying him—even at one point stealing away the reels of his

edit from the cutting room into a waiting pickup truck. The story may be apocryphal, but when Sam’s cut turned up on

Los Angeles’ Z-Channel, it came directly from Sam’s hand—from his own “personal archives.”

On to page 2 >

|