|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

By Geof Smith

In 1991, actor Charlie Sheen came into possession of a video showing the abduction, brutal torture and gory

disembowelment of a young Japanese woman by a man in a samurai costume. Convinced the gruesome images were

real, he contacted the FBI and learned that an investigation was already underway with the aid of the Japanese

police. The investigation revealed that the tape was actually a bootleg of Flower of Flesh and Blood, the

second installment in a Japanese horror series known as Guinea Pig. The actress was alive and well, and so

it seems was the myth of the snuff film.

Since the early seventies rumors have persisted that murders are routinely filmed and circulated among a

shadowy clientele hungry for the most extreme forms of "entertainment." However, time and again, these

claims are proven false; or, if a movie is located, the execution is quickly exposed as a fake. Law enforcement

from New York to Los Angeles—and on multiple continents—has yet to produce a real snuff movie or even evidence of one.

(Upright citizen Al Goldstein, publisher of Screw magazine, has a longstanding reward of $1 million for anyone

who can present a legitimate snuff film. To date, the money is unclaimed and probably will remain so considering

Goldstein's current financial state). Still the mere suggestion of these movies actually existing is enough to frighten and intrigue.

Like Bigfoot, (our underwater ally) Nessie and the probe-inserting alien grays, the snuff film myth has entered the popular psyche. No one has

seen the real thing, and only a minority of gore-hounds has sought out the fakes, yet most people know the

blueprint: grainy little movies shot in other countries where life is cheap; a woman tied to a filthy bed being

violated and ultimately dismembered by some Trog wearing a ski mask or stocking over his head. Over the years

certain snuff-film details have been tweaked—8mm film became replaced by videotape, South American locales have shifted to Japan or South

Africa—but the basic template has been repeated and reinforced by the media, rumor, and alarmists on the left and right. It all started with Charles Manson.

Much has been made about the Tate-LaBianca murders marking the end of the flower-power movement. That ending

also marked a beginning: the serial killer as pop star and a mainstream fascination not just with scandal

and lurid tabloid tales, but also with the mechanics of murder. A deluge of articles, books, and movies

explored and exploited the events and ensuing trial. Riding this flood was The Family: The Story of Charles

Manson's Dune Buggy Attack Battalion, by Ed Sanders, founder of the folk-rock band The Fugs. As the title

suggests, the book is an excitable combination of investigation and mythmaking. One piece of hearsay that

Sanders reports is that the Family was responsible for other murders—murders that were filmed. He referred

to these as "snuff" films, and an urban legend was christened.

Much has been made about the Tate-LaBianca murders marking the end of the flower-power movement. That ending

also marked a beginning: the serial killer as pop star and a mainstream fascination not just with scandal

and lurid tabloid tales, but also with the mechanics of murder. A deluge of articles, books, and movies

explored and exploited the events and ensuing trial. Riding this flood was The Family: The Story of Charles

Manson's Dune Buggy Attack Battalion, by Ed Sanders, founder of the folk-rock band The Fugs. As the title

suggests, the book is an excitable combination of investigation and mythmaking. One piece of hearsay that

Sanders reports is that the Family was responsible for other murders—murders that were filmed. He referred

to these as "snuff" films, and an urban legend was christened.

While it is true that police seized a camera loaded with unexposed film when they raided Spahn Ranch on

October 10, 1969, movies of murders were never located. This fact, however, did not really matter. After

a convulsive stretch of American history that witnessed not only Manson but also Viet Nam, Watergate, multiple

riots and televised assassinations, snuff didn't require much of an imaginative leap. As soon as the belief

took root, there were people eager to take advantage of it. Enter Allan Shackleton.

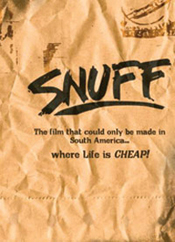

Shackleton promoted skin flicks and exploitation fare through his company Monarch Releasing Corporation.

With the news of snuff films he sensed an angle and played it to the hilt. He took a failure of a film

titled Slaughter, made a few key changes, hyped it with a provocative ad campaign—"Made in South America...where

life is cheap!"—and created the exploitation movie equivalent of Orson Welles's War of the Worlds radio broadcast.

Shackleton promoted skin flicks and exploitation fare through his company Monarch Releasing Corporation.

With the news of snuff films he sensed an angle and played it to the hilt. He took a failure of a film

titled Slaughter, made a few key changes, hyped it with a provocative ad campaign—"Made in South America...where

life is cheap!"—and created the exploitation movie equivalent of Orson Welles's War of the Worlds radio broadcast.

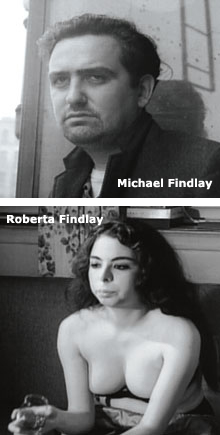

Throughout the sixties, the husband and wife filmmaking team of Michael and Roberta Findlay specialized in

roughies, pre-hardcore movies that didn't go all the way, but instead offered up heavy doses of flesh, fetish,

and kinky violence. In 1971 they attempted something slightly different—Slaughter, a tale of biker girls,

charismatic gurus, and hippie-cult murders that capitalized on the Manson hysteria. It was shot in Argentina

in four weeks with a budget of $30,000. The finished film was meandering, amateurish, and ultimately unreleasable.

It sat on a Monarch shelf until 1975 when Shackleton removed the opening credits, grafted a few minutes of

"shocking" footage onto the end, and re-titled the movie Snuff.

It sat on a Monarch shelf until 1975 when Shackleton removed the opening credits, grafted a few minutes of

"shocking" footage onto the end, and re-titled the movie Snuff.

In the new movie, at the seventy-four minute mark, the narrative suddenly breaks and the viewer sees what

appears to be behind-the-scenes footage. As the crew departs, the director puts his moves on a young woman.

His kissing turns aggressive. Other men emerge to help hold the struggling woman down. Additional angles

cover the violent action as her fingers are snipped off with shears; she's stabbed; and her intestines are

yanked out. Then just as the film runs out, the soundtrack catches the cameraman confirming that he 'got it.'

The additional footage is obviously faked. The set doesn't match the one from the final shots of the Slaughter

footage, and the bloody effects are pretty poor. The number of camera angles and convenient cuts are highly

suspicious for something supposedly shot on the fly. In fact, this supposedly black market footage looks more

capable than the preceding Findlay movie. This extra sequence is actually the work of one-eyed S&M filmmaker,

Malcolm Worob, and the most shocking thing about it is the controversy it generated.

As Snuff crawled from city to city, Shackleton made sure that furor and sensation accompanied it. He primed

the media with stories of the film's shady origins. He rallied citizens groups and feminist organizations to

picket the film. When they didn't show, he provided his own outraged throngs. Eventually word spread that

Snuff was not just a fraud, but, even worse, it was dreadfully dull. The uproar faded, but the movie grossed

millions-and that was before Merlin Mail marketed it to the first generation of home video enthusiasts steeped

in Snuff's notoriety.

The snuff myth did not fade. In fact, it flourished via the symbiotic relationship of a media looking to shock

and groups looking to protest—and no group did more to cultivate the myth than the feminist movement. Writers

like Gloria Steinem and Andrea Dworkin (right) portrayed snuff as the ultimate evil in a woman-hating culture, the

natural last rung on the ladder of pornographic descent. When porn-chic poster girl turned anti-porn crusader

turned centerfold Linda Lovelace spoke before the U.S. Attorney General's Commission on Organized Crime, she

The snuff myth did not fade. In fact, it flourished via the symbiotic relationship of a media looking to shock

and groups looking to protest—and no group did more to cultivate the myth than the feminist movement. Writers

like Gloria Steinem and Andrea Dworkin (right) portrayed snuff as the ultimate evil in a woman-hating culture, the

natural last rung on the ladder of pornographic descent. When porn-chic poster girl turned anti-porn crusader

turned centerfold Linda Lovelace spoke before the U.S. Attorney General's Commission on Organized Crime, she

included firsthand claims of genuine snuff rumors in her testimony. She revealed that women who were no longer

useful to the porn industry were routinely murdered both on and off camera. But Lovelace, like all the other outraged

voices, never produced hard evidence.

included firsthand claims of genuine snuff rumors in her testimony. She revealed that women who were no longer

useful to the porn industry were routinely murdered both on and off camera. But Lovelace, like all the other outraged

voices, never produced hard evidence.

When Cecil Adams wrangled with the snuff question in his syndicated column "The Straight Dope, he went to Ted

McIlvenny, director of the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality. McIlvenny, who has a collection

of more than 389,000 adult films, has studied pornography for over twenty-five years and has seen only three

instances of death on film:

"In two cases, the death was unintended: (1) a man dying of a heart attack during an S&M scene; and (2) a man accidentally strangled himself during an autoerotic asphyxiation. McIlvenny says the third film involving an actual death was a bizarre religious number from Morocco in which a hunchbacked kid was torn apart by wild horses while men stood around and masturbated."

—The Straight Dope, July 3, 1993

All of these would be shocking clips, particularly number three (unless you're a religious man from Morocco), but none were intended to be black market snuff.

Likewise, a number of "squish" videos seized by Scottish police in 1998 fall into a similar category. The videos

showed women in stages of undress crushing a variety of small rodents, frogs, snails and insects under their high

heels. Though unsavory, these videos are not uncommon—and they don't rate as snuff.

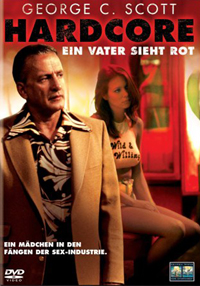

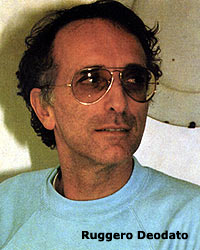

With all the hoopla, uproar and free advertising that Snuff created, other filmmakers were quick to join in. In

1976's Emmanuelle in America, Laura Gemser plays the titular swinging undercover journalist who discovers and

almost falls victim to a murky snuff ring in the Caribbean. In Paul Shrader's Hardcore it's George C. Scott

that uncovers a deadly world of sleaze while searching for his daughter in L.A.'s world of porn. And long before

The Blair Witch Project, Ruggero Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust created a movie, and a furor, with the supposedly

uncovered film of a ritually murdered documentary crew. After seeing Cannibal Holocaust, Italian auteur Sergio

Leone wrote to Deodato: "What a movie! The second part is a masterpiece of cinematographic realism, but everything

seems so real that I think you will get in trouble with all the world." This is one of the most succinct and

clear-headed appraisals of a decidedly difficult film.

With all the hoopla, uproar and free advertising that Snuff created, other filmmakers were quick to join in. In

1976's Emmanuelle in America, Laura Gemser plays the titular swinging undercover journalist who discovers and

almost falls victim to a murky snuff ring in the Caribbean. In Paul Shrader's Hardcore it's George C. Scott

that uncovers a deadly world of sleaze while searching for his daughter in L.A.'s world of porn. And long before

The Blair Witch Project, Ruggero Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust created a movie, and a furor, with the supposedly

uncovered film of a ritually murdered documentary crew. After seeing Cannibal Holocaust, Italian auteur Sergio

Leone wrote to Deodato: "What a movie! The second part is a masterpiece of cinematographic realism, but everything

seems so real that I think you will get in trouble with all the world." This is one of the most succinct and

clear-headed appraisals of a decidedly difficult film.

In the first half of Cannibal Holocaust an expedition searches for a missing crew of bad-boy documentarians

in the treacherous jungles of South America's "green inferno." Only skeletal remains and undeveloped film

are found. The canisters are returned to New York, where producers and broadcast executives view the footage.

Though the movie never suggests this found film is real, it is very verité and very disturbing. To make

matters more disquieting, Deodato borrows heavily from the mondo-movie tradition, including shots of actual

violence against animals and real political executions. This creates a toxic atmosphere that makes the later

sequences of rape, simulated tribal punishment and climactic cannibalism seem all the more real. Credit

also must go to editor Vincenzo Tomassi and effects-maestro Aldo Gasparri for their skillful work. As was

done in Snuff, they make use of fortuitous film breaks and convenient obstructions, but here the work is

nauseatingly flawless. So convincing, in fact, that French magazine Photo suggested Cannibal Holocaust

contained elements of real snuff. These rumors, plus the truly unsettling shots of turtle mutilation got

the movie banned in numerous countries. In Italy, a country known for its particularly potent exploitation

films, director Deodato spent three years fighting obscenity charges. He eventually won, and the international

notoriety ensured Cannibal Holocaust a long life as a home video and midnight-movie endurance test.

In the first half of Cannibal Holocaust an expedition searches for a missing crew of bad-boy documentarians

in the treacherous jungles of South America's "green inferno." Only skeletal remains and undeveloped film

are found. The canisters are returned to New York, where producers and broadcast executives view the footage.

Though the movie never suggests this found film is real, it is very verité and very disturbing. To make

matters more disquieting, Deodato borrows heavily from the mondo-movie tradition, including shots of actual

violence against animals and real political executions. This creates a toxic atmosphere that makes the later

sequences of rape, simulated tribal punishment and climactic cannibalism seem all the more real. Credit

also must go to editor Vincenzo Tomassi and effects-maestro Aldo Gasparri for their skillful work. As was

done in Snuff, they make use of fortuitous film breaks and convenient obstructions, but here the work is

nauseatingly flawless. So convincing, in fact, that French magazine Photo suggested Cannibal Holocaust

contained elements of real snuff. These rumors, plus the truly unsettling shots of turtle mutilation got

the movie banned in numerous countries. In Italy, a country known for its particularly potent exploitation

films, director Deodato spent three years fighting obscenity charges. He eventually won, and the international

notoriety ensured Cannibal Holocaust a long life as a home video and midnight-movie endurance test.

Unpleasant as it may be, Cannibal Holocaust reveals snuff to be an intriguing cinematic conceit and makes powerful

use of it in the process. Snuff isn't just murder, it's murder with a cameraman—and by extension a moviegoer—passively observing. When used effectively, it raises questions of responsibility and creates dramatic tension

between what's real and what's not. It's a concept Alfred Hitchcock would have loved. The same year Hitch mixed voyeurism

and serial murder in Psycho, British director Michael Powell did the same—except he gave his killer a 16mm camera.

The result, Peeping Tom, was an initially misunderstood masterpiece that has since provided thesis material for

many film students. So, though the myth was jumpstarted with hucksterism and hysteria, it's not surprising that

it grew into a compelling device. Throughout the 80s and 90s, films like Videodrome, Henry: Portrait

of a Serial Killer, 52 Pick-Up, Man Bites Dog, and 8mm used elements of the snuff legend to provide moments of

horror, irony, and pulpy intrigue. Larry Cohen's Special Effects puts an interesting spin on the set-up when

reality-obsessed filmmaker Chris Neville (Eric Bogosian) needs to cover up an on-camera murder by making it appear

faked. "What makes it different?" he wonders. "What if there is no difference: real death/make-believe death?"

There is, of course, a difference, and it is as a reminder of this fact that the snuff legend remains potent.

Unpleasant as it may be, Cannibal Holocaust reveals snuff to be an intriguing cinematic conceit and makes powerful

use of it in the process. Snuff isn't just murder, it's murder with a cameraman—and by extension a moviegoer—passively observing. When used effectively, it raises questions of responsibility and creates dramatic tension

between what's real and what's not. It's a concept Alfred Hitchcock would have loved. The same year Hitch mixed voyeurism

and serial murder in Psycho, British director Michael Powell did the same—except he gave his killer a 16mm camera.

The result, Peeping Tom, was an initially misunderstood masterpiece that has since provided thesis material for

many film students. So, though the myth was jumpstarted with hucksterism and hysteria, it's not surprising that

it grew into a compelling device. Throughout the 80s and 90s, films like Videodrome, Henry: Portrait

of a Serial Killer, 52 Pick-Up, Man Bites Dog, and 8mm used elements of the snuff legend to provide moments of

horror, irony, and pulpy intrigue. Larry Cohen's Special Effects puts an interesting spin on the set-up when

reality-obsessed filmmaker Chris Neville (Eric Bogosian) needs to cover up an on-camera murder by making it appear

faked. "What makes it different?" he wonders. "What if there is no difference: real death/make-believe death?"

There is, of course, a difference, and it is as a reminder of this fact that the snuff legend remains potent.

Snuff is the Frankenstein monster of the media age, the boogeyman that lurks at the crossroads of unchecked media

freedom and commercial demand. Each time a new technology makes questionable entertainment more accessible and

moral standards are questioned, the monster is awakened and the angry villagers ignite their torches. With the

new world of the web, the myth seems ready for an upgrade. In fact, as early as 1989, two Virginia men, Daniel

Depew and Dean Lambey, were arrested by the FBI after posting on a computer bulletin board (what a jury later decided was) a plan to

kidnap, molest, then kill a boy for a snuff film. This story exemplifies one of the key problems with the myth

of snuff: if someone is going to commit the ultimate crime, why create a record of that crime and make it public? Even serial

killers Leonard Lake and Charles Ng—who videotaped the sexual humiliation of two of their victims prior to killing them—never recorded

the actual murders. Still rumors persisted that these men captured the final moments of their nineteen victims

for distribution in Hong Kong. Similar stories of other killers keeping such souvenirs have been proven untrue

as well. Still, each new rumor is a reminder that just because it hasn't happened, doesn't mean it won't.

Though the persistent belief in the existence of snuff suggests pessimism about the human condition, there is something

oddly optimistic at the base of the hysteria. With snuff—and its shadowy conspiracy of criminals and jaded

perverts—there is a familiar structure, an evil that lawmakers and law-enforcement agencies feel can be easily identified and stopped. But for the other victim of snuff, the viewer, what is there to do in the face of random acts

of violence and chaos haphazardly captured on film?

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|