Richard Eagan:

Art, Bee-Keeping And Karaoke In Drag

By Jessica Myers-Schecter

Finding Richard Eagan was a bit of a challenge—there's no nameplate outside 295 Degraw, and I walked through the building

twice before asking one of the other artists if they knew where I could find Eagan's studio. A few turns and a short ramp later I found

him deep in conversation with another visitor to the Gowanus Open Studio Tour.

On the wall were several pieces that he calls "exploding canvases." Clusters of blood-red wood shards protrude from polished steel

shapes or, in the case of one piece, thrust through the confines of a wire cage. There's a certain violence to the pieces—a

combination, perhaps, of the blood color and sharp shards erupting toward the viewer.

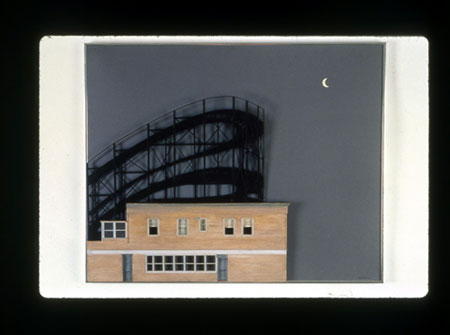

The exploding canvases form a new direction for Eagan, who first came to the public eye for his work known as architectural

portraiture and for his work as a founder of the Coney Island Hysterical Society, an artists' cooperative, in the 80's.

This new work developed in tandem with Eagan's emergence as a cross-dresser and adoption of alter personae Kay Sera. (He hosts a

popular karaoke series at Red Hook's Hope and Anchor every weekend night that won a "Best New Dinner Theater Award" from Time Out.)

And, as an unusual side business, he keeps bees at his upstate studio and now sells the honey under the label "Kay Sera."

Richard and I met several Saturdays after the Gowanus Open Studio Tour at his Park Slope abode to talk about the forces that led

him to his current renaissance as an artist and a performer.

Can you tell us a little about your earlier work—the architectural portraiture?

I started out as a cabinet maker and that's really what I did for the bulk of my non-artistic working life. And that experience,

in terms of the craft, influenced my work. I was working as a woodworker, raising a couple of kids, and kind of at sixes and sevens

as to what I really wanted to do. Then I had a series of dreams at the turn of the '80s about my grandfather and Coney Island.

I would see him disappearing through doorways and see him in these fantastic places we used to go when I was a kid. And so my

late wife said to me, "this is evidently important." You should do something about it. Well, I didn't know what I could do until

I realized I had these skills and that I loved these places and that I could do this. Work such as "Fred's House" emerged from

this experience.

What was your role in the Coney Island Hysterical Society?

Coney Island isn't just an amusement park, it's a place—a series of streets by the beach with a boardwalk that grew from the

late 1800s forward. It began as a beach resort and before there was air conditioning people would go out to Coney Island for

the summer and stay in hotels. It was quite different from the way it is now. In the 20th century it developed into what they

call the "nickel empire." There were amusements of all different kinds for blocks and blocks and blocks. Rides, attractions,

shows, dance halls, and beer parlors were all crammed into these old Victorian wooden buildings.

For many of us who'd grown up in Brooklyn, Coney Island was a kind of mythological playground. The buildings were magical places

because they were like the houses we grew up in, but phantasmagorical things went on there. But during the postwar years, and

especially during the 70s, the place began to hit the skids. There was tremendous gang warfare. Landowners and business owners

were having what was called "shortened cash registers." There were electrical fires… And we were hysterical to see our childhood

playground destroying itself. So several artists formed this arts organization. We did signage; we painted ride-fronts; we

painted carousel horses and eventually we renovated an old ghost ride and ran it as a combination amusement ride and art gallery

called the Coney Island Spookhouse.

But economically we couldn't keep it up. Eventually we sold it and I stayed on in Coney Island and worked for a number of years.

I met a guy named Dick Ziguns who runs a place called "Sideshows By The Seashore," which is the last authentic old-fashioned side

show left in the country. I was a barker on a live thrill show involving this woman from Belgium who swam with sharks. I ran

quarter pitch games. I did all kinds of things.

But economically we couldn't keep it up. Eventually we sold it and I stayed on in Coney Island and worked for a number of years.

I met a guy named Dick Ziguns who runs a place called "Sideshows By The Seashore," which is the last authentic old-fashioned side

show left in the country. I was a barker on a live thrill show involving this woman from Belgium who swam with sharks. I ran

quarter pitch games. I did all kinds of things.

I wrote and still perform from time to time a play for one actor with multiple characters called "Alive On The Inside," which is

about my experience growing up in Brooklyn, going to Coney Island, leaving it all behind and then coming back as an adult and as

an artist desperate to see that Coney Island didn't disappear.

And how did this type of work bridge to your current work—the "exploding canvases" that will be on display at

440 Gallery in January?

When I was working in Coney Island I had this notion of seeing paintings in which something was bursting out of the picture

plane. We worked with a material commonly used by display makers. It impregnated the canvas; you'd paint the surface with this

solution and it would harden. I kept imaging these canvases in which the surface would burst out toward the viewer. So that it

would seem as if stuff were pouring out of the canvas. At the time I never stopped to work that idea out or engineer it. But

in the last few years I've had this studio down here on 13th St. [in Park Slope, Brooklyn] and I had a number of small canvases.

I've started to work with that idea, albeit on a small scale, and that's how these "exploding" canvases came to be.

Right now I'm exploring similar ideas on slightly larger canvases. This led to the aluminum and wood pieces you saw at the

Gowanus Studio Tour. In those pieces I took sheet aluminum and glued it onto a plywood substrate just as you would say lay down

Formica on a kitchen counter. The paint is acrylic. I also use dollhouse pieces-such as a window or doorframe and miniature siding.

Some people say the pieces seem violent. But you know its funny because it doesn't make sense to me. I mean I am exploding

outward, I suppose. I've come out as a cross-dresser. Yet I am experiencing personally tremendous peace, joy, and serenity.

So it doesn't make sense emotionally speaking. But it is what it is. And when the work doesn't make sense-that's when you have

to pursue it. When I look at something that I'm doing and say, "That's not me," then I know I'm on to something. What was internal

becomes external.

Another thing that's emerged is that some people look at one or two of the aluminum and wood pieces and think I'm using vaginal

imagery, which is bizarre because it's not something I've intended. But this came out during a phase in which I wasn't really

thinking about my intention per se. As Claes Oldenburg said, "Don't think just be working." I had no idea what I was doing. It was

almost like automatic writing. There was an unconscious level to it.

On to page 2 >

|