|

|

Shaping Fact & Fiction:

In Cold Blood from Page to Screen

By Rod Schecter

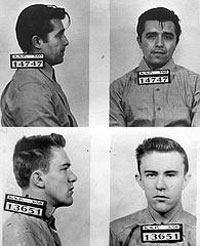

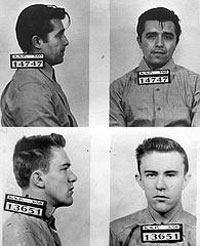

It’s hard to believe that this month marks the 46th anniversary of the Clutter murders, an act that ultimately led to the

death of six people (including the execution of the murders). Despite the rampant success of Law & Order, one still might think the

death of an average Kansas family to be marginal—if not banal, especially in the wake of Charlie Manson, Jeffrey Dahmer, and

murders on a catastrophic scale like 9/11. The fact remains, however, that the story of the Clutters and the two men to whom

they’d be linked forever, their murderers Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, is still as bizarre and harrowing as it was almost

fifty years ago.

Whether rendered in prose or in film there is something simple and striking about this story that keeps us fascinated with the

more primitive side of human nature and Brooks’s film, with the help of Quincy Jones’s disquieting score, does a exceptional

job of re-imagining Capote’s masterpiece while inventing a sleek and stylized shape of its own.

With the success of Bennett Miller’s Capote, it seems obvious that the New York City cultural gem Film Forum’s brief re-release

of the Richard Brooks feature film in the new 35mm scope print (accompanied by a one-time showing of the Maysles brothers’

documentary From Truman With Love), in addition to receiving some trickledown ticket sales, was intended to add a little more

texture to the legendary story of the Clutter murders that the original masterpiece created. This legend was to vehicle that

was to change the literary landscape when Capote reinventing the idea of journalism wearing a novel’s clothing—reportage or

the non-fiction novel. However, it is the extraordinary sense of texture that peppers these works that prevents them from being

two-dimensional. Not to say that Capote’s “novel” or Brooks’s film for that matter is two-dimensional (far from it), but by

viewing the subject matter through various forms (non-fiction novel, cinematic adaptation, cinema veritae documentary, and

autobiographical feature film adaptation—not to mention the entire cannon of critical and investigative literature on

this subject) one can begin to see prismatic structures emerging in 3D and beyond.

With the success of Bennett Miller’s Capote, it seems obvious that the New York City cultural gem Film Forum’s brief re-release

of the Richard Brooks feature film in the new 35mm scope print (accompanied by a one-time showing of the Maysles brothers’

documentary From Truman With Love), in addition to receiving some trickledown ticket sales, was intended to add a little more

texture to the legendary story of the Clutter murders that the original masterpiece created. This legend was to vehicle that

was to change the literary landscape when Capote reinventing the idea of journalism wearing a novel’s clothing—reportage or

the non-fiction novel. However, it is the extraordinary sense of texture that peppers these works that prevents them from being

two-dimensional. Not to say that Capote’s “novel” or Brooks’s film for that matter is two-dimensional (far from it), but by

viewing the subject matter through various forms (non-fiction novel, cinematic adaptation, cinema veritae documentary, and

autobiographical feature film adaptation—not to mention the entire cannon of critical and investigative literature on

this subject) one can begin to see prismatic structures emerging in 3D and beyond.

So, as Capote uses fact to shape a novel into a new art form, then Brooks’s adaptation creates yet another shape to contain the

original tragedy because he had to bend truth in order to translate the heart of Capote’s work into a feature film as slick

and tight as any of that era. However, what remains the same in all dimensions is exactly what our culture, and Capote himself,

finds so fascinating about the mind of the sociopath.

Just like Capote, Brooks is fixated not on the death of four law-abiding Americans, but on their attackers—principally the

impish “boy-man” Smith, who at some level receives both Capote’s and Brooks’s sympathy for a largely traumatic past. From the

constant attention to Smith’s disfigured legs caused by a “murdercycle” accident to the intense dream sequences that point out

abandonment, an abusive father, a drunk mother, and a frighteningly calm disconnect with the real world, what comes to the

surface is a penetrating insight into how and why such a mind becomes so disconnected. In this aspect, Brooks’s film succeeds in

capturing this fixation from the opening shot of Robert Blake as Perry Smith draped in shadow on the back a moving bus, his

infamous cat paw boots glittering like diamonds on jewelers’ velvet, to the cinematic stamp of Robert Blake’s final monologue,

his face a backdrop for the pallid reflections of the rain colliding with the moon-lit window beside him.

Just like Capote, Brooks is fixated not on the death of four law-abiding Americans, but on their attackers—principally the

impish “boy-man” Smith, who at some level receives both Capote’s and Brooks’s sympathy for a largely traumatic past. From the

constant attention to Smith’s disfigured legs caused by a “murdercycle” accident to the intense dream sequences that point out

abandonment, an abusive father, a drunk mother, and a frighteningly calm disconnect with the real world, what comes to the

surface is a penetrating insight into how and why such a mind becomes so disconnected. In this aspect, Brooks’s film succeeds in

capturing this fixation from the opening shot of Robert Blake as Perry Smith draped in shadow on the back a moving bus, his

infamous cat paw boots glittering like diamonds on jewelers’ velvet, to the cinematic stamp of Robert Blake’s final monologue,

his face a backdrop for the pallid reflections of the rain colliding with the moon-lit window beside him.

While Smith’s acceptance of his father’s abuse in this scene, and his ability to simultaneously “love and hate him,” seems to

be a heavy-handed device used, in part, to explain how someone who seems so sensitive, lucid, and childlike (wide-eyed at stories

of gold and glory), can also become so explosively violent and unfeeling, this denouement brings home at least some explanation

of Perry Smith’s pathological and often contradictory behavior: how he could callously cut Herb Clutter’s throat in a heartbeat

but also prevent Hickock from raping Nancy Clutter before her death because he can’t stand “degenerate” sexual impulses.

Brooks does stay true to Capote’s book by masterfully weaving together the parallel plot lines that contrast the ex-cons’

first meeting in Kansas and their seedy, noir-like existence with the Clutter’s humdrum routine until their fates ultimately

and painfully intersect in a very dramatic and fast-paced montage that makes this picture a shamefully fiendish delight.

In this way the shape of Brook’s film mimics the novel’s ambition in that it makes us outraged at the tragedy but also hungry

to see more of Smith and Hickock’s journey, so hungry in fact that, despite their pasts, we can even take joy in their now-famous

bottle scene, where Smith and a young hitchhiker scout soda bottles for money on a Texas freeway, much in the same fanciful and

childish way Smith envisions hunting for treasure off the coast of Mexico. What emerges is both empathy and disgust for the

killers as we rubberneck through the rest of their ride, from their arrest until the final heart-pounding moment that we all

realize is awaiting them.

In this way the shape of Brook’s film mimics the novel’s ambition in that it makes us outraged at the tragedy but also hungry

to see more of Smith and Hickock’s journey, so hungry in fact that, despite their pasts, we can even take joy in their now-famous

bottle scene, where Smith and a young hitchhiker scout soda bottles for money on a Texas freeway, much in the same fanciful and

childish way Smith envisions hunting for treasure off the coast of Mexico. What emerges is both empathy and disgust for the

killers as we rubberneck through the rest of their ride, from their arrest until the final heart-pounding moment that we all

realize is awaiting them.

What is more interesting, however, is how Brooks finds a delicate and succinct way to twist the truth of Capote’s genre-bending

work to fit the power of this story into a more popularized form. While the film adequately captures the tension of the book,

at times it fails to embody what Capote himself did so successfully—which was to give a voice not only to the primary players

but the entire town—and thus our culture, whether it’s the gossip in a small town coffee shop or the headline branding of the

main stream media. By using this town as a character, it’s inhabitants as the many voices, Capote lays down a collage style of

storytelling, allowing us to glean information from the various juxtapositions and the spaces in between.

Instead, Brooks gives us an immediate, smoothly edited, and singular present-tense narrative that eschews the subjectivity of

collective human perception. Brooks tells this story with the unified vision of the camera’s eye, which does a fine job of

streamlining the essential parts but ultimately fails in doing what the book manages to do—render the crime into a shape that

Robert Blake’s Smith ironically describes as a “third” personality with a life of its own, existing as much more than the sum

of its parts: the very disturbed Hickock and Smith.

What the film does well is heighten our fascination with the cult of personality associated with our celebrity-killer culture

and brings into focus the questions that we are always left asking: Why? Why did they do it when the “perfect score” turned out

to be a bust? (Rather than the fortune they expected, Smith and Hickock succeeded in getting away with fifty dollars and a radio.)

Why, or rather what made them into heartless criminals? And why are we more interested in the lives of the killers instead of the

victims—a poor family named Clutter who lost everything in their diligent, almost blind-eyed, pursuit of American promise?

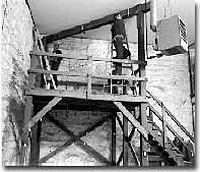

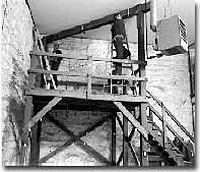

According to the Maysles brothers’ documentary, which turns the examiner into the examined in yet another twist of point of

view, Capote discusses at great length how the fully-realized shape of this novel was essential in giving the act that took

six lives its multifaceted texture—a texture that exists beyond the pages of his book or Brooks’s new 35mm scope print. In

other words, he transforms tragedy into art—into something beautiful in its construction—by manipulating its shape. In this way,

despite the film’s minor flaws, Brooks uses the same elements of tragedy to create a uniquely cinematic—and beautiful—body that

delivers us yet another “fully-realized” artistic dream.

According to the Maysles brothers’ documentary, which turns the examiner into the examined in yet another twist of point of

view, Capote discusses at great length how the fully-realized shape of this novel was essential in giving the act that took

six lives its multifaceted texture—a texture that exists beyond the pages of his book or Brooks’s new 35mm scope print. In

other words, he transforms tragedy into art—into something beautiful in its construction—by manipulating its shape. In this way,

despite the film’s minor flaws, Brooks uses the same elements of tragedy to create a uniquely cinematic—and beautiful—body that

delivers us yet another “fully-realized” artistic dream.

|

|

With the success of Bennett Miller’s Capote, it seems obvious that the New York City cultural gem Film Forum’s brief re-release

of the Richard Brooks feature film in the new 35mm scope print (accompanied by a one-time showing of the Maysles brothers’

documentary From Truman With Love), in addition to receiving some trickledown ticket sales, was intended to add a little more

texture to the legendary story of the Clutter murders that the original masterpiece created. This legend was to vehicle that

was to change the literary landscape when Capote reinventing the idea of journalism wearing a novel’s clothing—reportage or

the non-fiction novel. However, it is the extraordinary sense of texture that peppers these works that prevents them from being

two-dimensional. Not to say that Capote’s “novel” or Brooks’s film for that matter is two-dimensional (far from it), but by

viewing the subject matter through various forms (non-fiction novel, cinematic adaptation, cinema veritae documentary, and

autobiographical feature film adaptation—not to mention the entire cannon of critical and investigative literature on

this subject) one can begin to see prismatic structures emerging in 3D and beyond.

With the success of Bennett Miller’s Capote, it seems obvious that the New York City cultural gem Film Forum’s brief re-release

of the Richard Brooks feature film in the new 35mm scope print (accompanied by a one-time showing of the Maysles brothers’

documentary From Truman With Love), in addition to receiving some trickledown ticket sales, was intended to add a little more

texture to the legendary story of the Clutter murders that the original masterpiece created. This legend was to vehicle that

was to change the literary landscape when Capote reinventing the idea of journalism wearing a novel’s clothing—reportage or

the non-fiction novel. However, it is the extraordinary sense of texture that peppers these works that prevents them from being

two-dimensional. Not to say that Capote’s “novel” or Brooks’s film for that matter is two-dimensional (far from it), but by

viewing the subject matter through various forms (non-fiction novel, cinematic adaptation, cinema veritae documentary, and

autobiographical feature film adaptation—not to mention the entire cannon of critical and investigative literature on

this subject) one can begin to see prismatic structures emerging in 3D and beyond.

Just like Capote, Brooks is fixated not on the death of four law-abiding Americans, but on their attackers—principally the

impish “boy-man” Smith, who at some level receives both Capote’s and Brooks’s sympathy for a largely traumatic past. From the

constant attention to Smith’s disfigured legs caused by a “murdercycle” accident to the intense dream sequences that point out

abandonment, an abusive father, a drunk mother, and a frighteningly calm disconnect with the real world, what comes to the

surface is a penetrating insight into how and why such a mind becomes so disconnected. In this aspect, Brooks’s film succeeds in

capturing this fixation from the opening shot of Robert Blake as Perry Smith draped in shadow on the back a moving bus, his

infamous cat paw boots glittering like diamonds on jewelers’ velvet, to the cinematic stamp of Robert Blake’s final monologue,

his face a backdrop for the pallid reflections of the rain colliding with the moon-lit window beside him.

Just like Capote, Brooks is fixated not on the death of four law-abiding Americans, but on their attackers—principally the

impish “boy-man” Smith, who at some level receives both Capote’s and Brooks’s sympathy for a largely traumatic past. From the

constant attention to Smith’s disfigured legs caused by a “murdercycle” accident to the intense dream sequences that point out

abandonment, an abusive father, a drunk mother, and a frighteningly calm disconnect with the real world, what comes to the

surface is a penetrating insight into how and why such a mind becomes so disconnected. In this aspect, Brooks’s film succeeds in

capturing this fixation from the opening shot of Robert Blake as Perry Smith draped in shadow on the back a moving bus, his

infamous cat paw boots glittering like diamonds on jewelers’ velvet, to the cinematic stamp of Robert Blake’s final monologue,

his face a backdrop for the pallid reflections of the rain colliding with the moon-lit window beside him.

In this way the shape of Brook’s film mimics the novel’s ambition in that it makes us outraged at the tragedy but also hungry

to see more of Smith and Hickock’s journey, so hungry in fact that, despite their pasts, we can even take joy in their now-famous

bottle scene, where Smith and a young hitchhiker scout soda bottles for money on a Texas freeway, much in the same fanciful and

childish way Smith envisions hunting for treasure off the coast of Mexico. What emerges is both empathy and disgust for the

killers as we rubberneck through the rest of their ride, from their arrest until the final heart-pounding moment that we all

realize is awaiting them.

In this way the shape of Brook’s film mimics the novel’s ambition in that it makes us outraged at the tragedy but also hungry

to see more of Smith and Hickock’s journey, so hungry in fact that, despite their pasts, we can even take joy in their now-famous

bottle scene, where Smith and a young hitchhiker scout soda bottles for money on a Texas freeway, much in the same fanciful and

childish way Smith envisions hunting for treasure off the coast of Mexico. What emerges is both empathy and disgust for the

killers as we rubberneck through the rest of their ride, from their arrest until the final heart-pounding moment that we all

realize is awaiting them.

According to the Maysles brothers’ documentary, which turns the examiner into the examined in yet another twist of point of

view, Capote discusses at great length how the fully-realized shape of this novel was essential in giving the act that took

six lives its multifaceted texture—a texture that exists beyond the pages of his book or Brooks’s new 35mm scope print. In

other words, he transforms tragedy into art—into something beautiful in its construction—by manipulating its shape. In this way,

despite the film’s minor flaws, Brooks uses the same elements of tragedy to create a uniquely cinematic—and beautiful—body that

delivers us yet another “fully-realized” artistic dream.

According to the Maysles brothers’ documentary, which turns the examiner into the examined in yet another twist of point of

view, Capote discusses at great length how the fully-realized shape of this novel was essential in giving the act that took

six lives its multifaceted texture—a texture that exists beyond the pages of his book or Brooks’s new 35mm scope print. In

other words, he transforms tragedy into art—into something beautiful in its construction—by manipulating its shape. In this way,

despite the film’s minor flaws, Brooks uses the same elements of tragedy to create a uniquely cinematic—and beautiful—body that

delivers us yet another “fully-realized” artistic dream.