DIRTY SECRETS:

The Downtown Days of Art and Decadence

Dee Dee Vega

Rimbaud Was the Rage…

The first image I saw when thumbing through the catalogue for The Downtown Show was one from David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in

New York series of photographs from 1977. The photos of this series are in and of themselves striking. Stark black and white

images of Wojnarowicz’s friends wearing a mask of Rimbaud’s portrait seated on a dingy mattress, shooting up, riding the subway.

They have a delicate loneliness that reeks of Wojnarowicz pain and isolation while suffering from AIDS (which eventually killed

him). But the reason these photographs are an interesting key into understanding the downtown art movement is not because of

Wojnarowicz—but rather because of Rimbaud. There has been a tremendous interest in the culture seen of the seventies and eighties

in recent years. Art exhibitions on design aesthetics, documentaries on heroin-honey rockers (before the term “heroin chic”

even existed), and fashion redux is rife. It seems that in the East Village of today where the old half-way house on St. Marks

is now a Quiznos and you need to wear a tie to work or have a rich daddy to live on the Lower East Side—we are aching for the

They have a delicate loneliness that reeks of Wojnarowicz pain and isolation while suffering from AIDS (which eventually killed

him). But the reason these photographs are an interesting key into understanding the downtown art movement is not because of

Wojnarowicz—but rather because of Rimbaud. There has been a tremendous interest in the culture seen of the seventies and eighties

in recent years. Art exhibitions on design aesthetics, documentaries on heroin-honey rockers (before the term “heroin chic”

even existed), and fashion redux is rife. It seems that in the East Village of today where the old half-way house on St. Marks

is now a Quiznos and you need to wear a tie to work or have a rich daddy to live on the Lower East Side—we are aching for the

time of decadence where art and music filled the streets along with the stench of death and style. But still, even our heroes

had heroes. Rimbaud was revered not just by Wojnarowicz, but even New York Doll David Johansen looked to Rimbaud’s life and

poetry for lyrical inspiration. Why? Because he was a long-dead destroyer of the establishment as well as an artistic genius

who partied hard and died young. In that light, it isn’t hard to understand what is going on now.

time of decadence where art and music filled the streets along with the stench of death and style. But still, even our heroes

had heroes. Rimbaud was revered not just by Wojnarowicz, but even New York Doll David Johansen looked to Rimbaud’s life and

poetry for lyrical inspiration. Why? Because he was a long-dead destroyer of the establishment as well as an artistic genius

who partied hard and died young. In that light, it isn’t hard to understand what is going on now.

The idea that “sometimes the only thing worse not than getting what you want is getting it” has proved to be a concept oddly

fitting of the recent influx of art exhibitions in New York that seek to capture that exhilarating era when punk was born,

activism was hip and art pushed beyond the New York School-established comfort zone. When I visited The Downtown Show, curated

and housed at the Grey Gallery owned by New York University, it seemed so oddly incongruous that crowds were flocking to see

the cultural corpses of a past time at the financial juggernaut responsible for so much of the rancid gentrification of the

East Village (not to mention the very geniuses who turned Palladium into a dorm.) Not to mince words—but NYU sucked the

lifeblood out of downtown and I find it odd that they would seek to capitalize on a scene they helped to destroy.

Still, the vibrancy and revolution of New York art created between the years 1974 and 1984 is so strong that not even the

avaricious context of NYU can dampen its impact. The Downtown Show is a vast collection of the artwork, clothes and cultural

artifacts that begin with the enactment of the 1974 Loft Law which allowed artists to inhabit the industrial landscape and

spaces downtown to the re-election of Reagan marking the rightward descent to hell we seem to be revisiting. Both the strength

and weakness of the mammoth exhibition which consists of over four hundred pieces of art and cultural artifacts lies in its

curation. Any lover of this epoch, whether you experienced it or not, cannot help be dazzled by a journal, half filled, given

by Patti Smith to Richard Hell, Adrian Piper’s famous “Dear Friends cards” or a Max’s Kansas City menu with the doodles of

Robert Smithson—all institutions in their own right by now. Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud mask, in fact, is in the exhibition with

materials listed as “Magic marker on photocopy with rubber bands.” (Although it should be said that while the material listing

seems absurd, the 2-D black and white mask within the three dimensional physical space against the flat picture plane of the

photograph is incredibly compelling.) While the exhibition excels in it’s collection of pieces, in her introductory catalogue

essay, curator Lynn Gumpert openly admits to being “resolutely a morning person never keen on nightclubs” and largely unaware

that the punk scene even existed at the time. And it shows. While the catalogue sites Fashion Moda for it’s revolutionary

use of a dirty, unconventional space with (gasp!) visible nail holes in the exhibition rooms and info text written directly

on the wall—the Grey Gallery is pristine as can be. Although the catalogue balances it’s academia with credibility by the

likes of the perspectives of Lydia Lunch and Eric Bogosian who undoubtedly experienced the real thing.

Still, the vibrancy and revolution of New York art created between the years 1974 and 1984 is so strong that not even the

avaricious context of NYU can dampen its impact. The Downtown Show is a vast collection of the artwork, clothes and cultural

artifacts that begin with the enactment of the 1974 Loft Law which allowed artists to inhabit the industrial landscape and

spaces downtown to the re-election of Reagan marking the rightward descent to hell we seem to be revisiting. Both the strength

and weakness of the mammoth exhibition which consists of over four hundred pieces of art and cultural artifacts lies in its

curation. Any lover of this epoch, whether you experienced it or not, cannot help be dazzled by a journal, half filled, given

by Patti Smith to Richard Hell, Adrian Piper’s famous “Dear Friends cards” or a Max’s Kansas City menu with the doodles of

Robert Smithson—all institutions in their own right by now. Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud mask, in fact, is in the exhibition with

materials listed as “Magic marker on photocopy with rubber bands.” (Although it should be said that while the material listing

seems absurd, the 2-D black and white mask within the three dimensional physical space against the flat picture plane of the

photograph is incredibly compelling.) While the exhibition excels in it’s collection of pieces, in her introductory catalogue

essay, curator Lynn Gumpert openly admits to being “resolutely a morning person never keen on nightclubs” and largely unaware

that the punk scene even existed at the time. And it shows. While the catalogue sites Fashion Moda for it’s revolutionary

use of a dirty, unconventional space with (gasp!) visible nail holes in the exhibition rooms and info text written directly

on the wall—the Grey Gallery is pristine as can be. Although the catalogue balances it’s academia with credibility by the

likes of the perspectives of Lydia Lunch and Eric Bogosian who undoubtedly experienced the real thing.

While the ephemera and objects in the exhibition are certainly dazzling (if not nostalgic)—the deliberately blurred distinction

of “fine art” by artists at the time is also readily apparent. Chuck Close’s portrait fashioned from of thumb prints of

Philip Glass is displayed beside Roberta Bayley’s photograph of Legs McNeil, Andy Warhol and Richard Hell. Cindy Sherman’s

Untitled Film Still is next to Bob Gruen’s Lipstick Killers shot of the New York Dolls. (Gruen’s some forty hours of footage

of the Dolls has also recently been released on DVD.) The evolution of some of these figures into the cold halls of the fine

art canon and some into the sordid walls of CBGB’s gallery is pointed in these juxtapositions. Whose side you’d rather be

on is up to you.

While the ephemera and objects in the exhibition are certainly dazzling (if not nostalgic)—the deliberately blurred distinction

of “fine art” by artists at the time is also readily apparent. Chuck Close’s portrait fashioned from of thumb prints of

Philip Glass is displayed beside Roberta Bayley’s photograph of Legs McNeil, Andy Warhol and Richard Hell. Cindy Sherman’s

Untitled Film Still is next to Bob Gruen’s Lipstick Killers shot of the New York Dolls. (Gruen’s some forty hours of footage

of the Dolls has also recently been released on DVD.) The evolution of some of these figures into the cold halls of the fine

art canon and some into the sordid walls of CBGB’s gallery is pointed in these juxtapositions. Whose side you’d rather be

on is up to you.

There are equally interesting attempts to include intentionally trashy art—high kitsch indeed—in the “Salon de Refuse” section.

In a recent New York Times review, writer Grace Glueck fancies the trend as an attempt at to subvert Clement Greenberg’s

stranglehold on critical perception. I feel it more a nod to King Andy and an obvious consequence of the emergence of entities

such as Keith Haring’s Pop Shop and the Kenny Scharf-enfused club culture —far more based in playfulness than a “fuck you” to

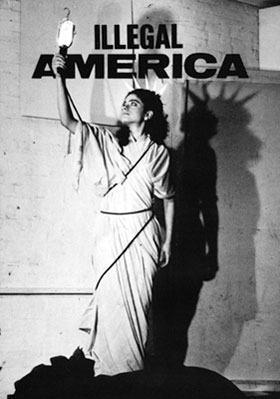

Clem. The Downtown Show also features a “Body Politic” installment that places the art of the era within the rising political

consciousness for queer, feminist and AIDS activism. Porn stars like Annie Sprinkle, performers Klaus Nomi and Ethyl

Eichelberger and documentation of Karen Findley speak to the breath of innovation and commitment to creating a new

socio-artistic vocabulary for activism. Although work by Tim Rollins & K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) are featured in the

“Broken Stories” section dedicated to text and literary works, the thread of social awareness and the desire to make an

art connected with the experience of the street resonates in these gestures as well as the obvious Basquiat-helmed

guerilla graffiti movement that has emerged as one of the most pervasive and far-reaching trends of the period.

There are equally interesting attempts to include intentionally trashy art—high kitsch indeed—in the “Salon de Refuse” section.

In a recent New York Times review, writer Grace Glueck fancies the trend as an attempt at to subvert Clement Greenberg’s

stranglehold on critical perception. I feel it more a nod to King Andy and an obvious consequence of the emergence of entities

such as Keith Haring’s Pop Shop and the Kenny Scharf-enfused club culture —far more based in playfulness than a “fuck you” to

Clem. The Downtown Show also features a “Body Politic” installment that places the art of the era within the rising political

consciousness for queer, feminist and AIDS activism. Porn stars like Annie Sprinkle, performers Klaus Nomi and Ethyl

Eichelberger and documentation of Karen Findley speak to the breath of innovation and commitment to creating a new

socio-artistic vocabulary for activism. Although work by Tim Rollins & K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) are featured in the

“Broken Stories” section dedicated to text and literary works, the thread of social awareness and the desire to make an

art connected with the experience of the street resonates in these gestures as well as the obvious Basquiat-helmed

guerilla graffiti movement that has emerged as one of the most pervasive and far-reaching trends of the period.

While the exhibition does have a significant number of video pieces well worth your time (Anne Magnuson’s 1984 Made for TV

video is not to be missed simply for her clothes)—there has recently been a documentary renaissance of films and footage that

chronicle the downtown scene, particularly the art music (Philip Glass, Terry Riley and Steve Reich) and the ubiquitously

influential punk and glam movement born with the Velvets and extending through the tragically hip and genuinely anti-commercial

New York Dolls, Blondie, Voidoids, Heartbreakers and the Ramones who were sleeping in lofts and streets and defining the new

American music while never seeming to gain mainstream recognition. Several years ago, the mysterious “lost reel” of

Downtown 81 was rediscovered in a French apartment. The film stars a fresh, fast-talking Jean Michel Basquiat as an artist

sliding through the deteriorated Lower East Side and the fashion parade of The Mudd Club and Peppermint Lounge. The film was

finally edited and released kicking off a slew of films that capture the depravity, decadence and new jack notoriety of the

Village and it’s inhabitants. A documentary on Arthur Kane, End of the Century about the Ramones, as well as the

aforementioned compilation of Bob Gruen’s unending hours of Dolls concert footage have all been circulated in the

quasi-mainstream and serve to capture the essence of the outré life as it was—as it shall never be seen again. The

desire to see it alive again is almost masturbatory. We want to create again. We want to make the birth of the cool.

They looked to Rimbaud. And to whom shall we look to light that spark? Bogosian seems to sum it up best, “It was like a

fire that creates more fire, until no one’s sure how it got started in the first place.” I say, let’s get down and make

art that burns hot.

While the exhibition does have a significant number of video pieces well worth your time (Anne Magnuson’s 1984 Made for TV

video is not to be missed simply for her clothes)—there has recently been a documentary renaissance of films and footage that

chronicle the downtown scene, particularly the art music (Philip Glass, Terry Riley and Steve Reich) and the ubiquitously

influential punk and glam movement born with the Velvets and extending through the tragically hip and genuinely anti-commercial

New York Dolls, Blondie, Voidoids, Heartbreakers and the Ramones who were sleeping in lofts and streets and defining the new

American music while never seeming to gain mainstream recognition. Several years ago, the mysterious “lost reel” of

Downtown 81 was rediscovered in a French apartment. The film stars a fresh, fast-talking Jean Michel Basquiat as an artist

sliding through the deteriorated Lower East Side and the fashion parade of The Mudd Club and Peppermint Lounge. The film was

finally edited and released kicking off a slew of films that capture the depravity, decadence and new jack notoriety of the

Village and it’s inhabitants. A documentary on Arthur Kane, End of the Century about the Ramones, as well as the

aforementioned compilation of Bob Gruen’s unending hours of Dolls concert footage have all been circulated in the

quasi-mainstream and serve to capture the essence of the outré life as it was—as it shall never be seen again. The

desire to see it alive again is almost masturbatory. We want to create again. We want to make the birth of the cool.

They looked to Rimbaud. And to whom shall we look to light that spark? Bogosian seems to sum it up best, “It was like a

fire that creates more fire, until no one’s sure how it got started in the first place.” I say, let’s get down and make

art that burns hot.

|