By Douglas Singleton

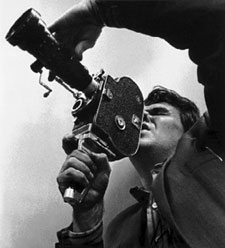

Avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage died at the age of 70 in 2003 and his passing was felt greatly throughout

the film and art worlds. Brakhage was one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, his explorations

into film abstraction were some of the purest displays of devotion to artistic principles one is likely to find.

Back in Chicago a number of years ago, my roommate was completing an MFA in film and new media studies at the

School of the Art Institute of Chicago. It was here that I first heard names like Maya Deren, Jonas Mekas,

Harry Smith, and often, most often, "Brakhage." He was held in such high esteem that his work took on a mythic

aura before I'd ever seen any of his films.

My curiosity with Brakhage's work lies in his progression from "realistic" film imagery (i.e. people, architecture, nature)

to abstraction fashioned through superimposition and rapid film cutting (even more so than Godard's MTV-

anticipating À Bout De Soufflé) and eventually on to pure abstraction by way of physically transforming film stock

by painting onto and "scratching" the surface of raw film. Progressively, he perfected this process and aesthetic

approach until he'd gotten to a point in late films of his career such as the Ellipses series where this form of

abstraction was the sole manner in which he wanted to create a logical progression. Some of Brakhage's health problems

were a result of this technique of applying paint directly to film stock or scratching the emulsion off of film-he

suffered a little for the art. Poet Steve Dalachinsky, a friend of Brakhage's, spoke at a tribute held at the

alternative space Galapagos in Brooklyn, New York, shortly after his death where he recalled spying Brakhage

scratching onto film stock whenever he got a moment away from his friends.

The program at Galapagos included an early example of Brakhage, In Between (1955), with music by John Cage. The

film is not necessarily representative of his work. It seems staged, an almost "Technicolor" feel to it, with ample

sound and musical accompaniment as opposed to his silent diary films, Window Water Baby Moving (1959) or Loving (1957)

with deconstructed/reconstructed images of he and his family. Wonder Ring (1955) is a silent piece he made in

collaboration with American surrealist artist Joseph Cornell, in which Brakhage took a 16mm camera onto the elevated

train line that ran along Third Avenue in New York City months before it was to be torn down. The film is a beautiful,

flowing assemblage of subway car imagery, the rail line itself, buildings viewed out of the windows of trains and

twilight abstractions of people moving in and out of subway stations circa the 50s. It is a hauntingly beautiful film,

a chronicle of human architecture and urban experience abstracted into elegiac, visual poetry.

By Mothlight, (1963), Brakhage was comfortable working in sumptuous color having abandoned recognizable imagery.

He created abstraction by manipulating film stock-in this case with moth wings applied directly to the film stock

heated with light. Mothlight is an organically beautiful watershed. But, of course, it was just the beginning-the

film is only four minutes long.

Dog Star Man (1961-1964) can be interpreted as a culmination of all of Brakhage's work, representative of his whole

oeuvre, the various styles-diarist family log, cinematic narcissism, meditations on space, the usurpation of both

time and visual expectation and the physical manipulation of film stock. It is a cycle of films consisting of a prelude

and four "chapters" and runs approximately an hour. It indeed requires some mental diligence to get through. These

films exhibit significant technical virtuosity, a synthesis of Brakhage's techniques up to that point in his career.

He then took off into the stratosphere: stark images of the cosmos and exploding stars, pumping organs within the

body, his wife breastfeeding their child, nature, nudity, sex, Brakhage himself endlessly climbing a mountain in the

snow, struggling with his dog at his side. Multiple superimpositions, fades, black screens, all juxtaposed with some

of his most eloquent film treatment techniques are on ample display.

Stan Brakhage felt that cinema, film, could be music. Not musical, like Welles or Chaplin, but actual music, a piece

of sui generis art in itself. Many of his works have more in common with Jackson Pollock than they do with

cinema-"motion" drip paintings. Mekas recalled Brakhage relating a story in which a "spiritualist" told Brakhage

that he could beat the cancer eating away at him by "channeling into his body" and confronting the cancerous cells

one at a time. Brakhage said that eventually he was indeed able to get inside of himself and confront the cells eating

away at his body, but that when he did so he could not destroy them-he found them too beautiful. He let them alone. I

suspect that even these made it into his work, perhaps as the stars of his films.

|