fRINGE INTERVIEW

GHOSTS OF MISSISSIPPI:

Director KEITH BEAUCHAMP talks about

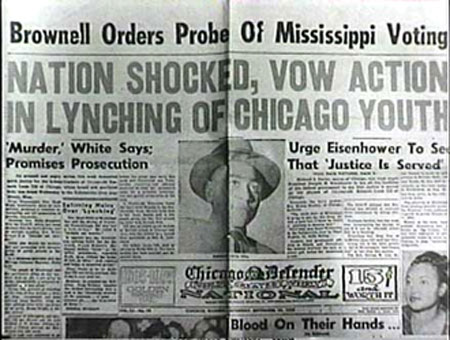

THE UNTOLD STORY OF EMMETT LOUIS TILL

By Dee Dee Vega

“Let the people see what I have seen. I think everybody needs to know what happened to Emmett Till.”

These are the words of Mamie Till-Mobley as she stood over the disfigured corpse of her son Emmett Till. Mrs. Mobley was

insisting on an open-casket funeral for her fourteen-year-old son whom she had accompanied to the train station over a week

earlier to take a trip to his cousins’ in Mississippi only to have him delivered back to her in a sealed wooden crate. Over 50,000

people back in the Till’s home of Chicago would attend Emmett’s funeral and the vicious murder of this child would become

the spark that started the fire of the civil rights movement.

Emmett was visiting his cousins at the end of the summer of 1955 in Money, Mississippi. On August 24th, along with several other children, Emmett and his cousins went into town, which only consisted of four buildings, to buy some candy after a day of picking cotton.

It was in the store that Emmett encountered Carolyn Bryant, wife of Roy Bryant, who was working in the store that afternoon. Whatever did transpire

inside the store—there is a credible living eyewitness who can attest that Emmett did place money directly into Carolyn’s

hand, rather than on the counter as he was “supposed” to do, which runs contrary to Carolyn Bryant’s testimony (that Emmett had grabbed her

around the waist and spoke to her in a lewd manner)—there's no doubt that Emmett exited the building and whistled at Bryant.

By August 31st, Mississippi authorities would drag the horribly disfigured body of Emmett Till from the Tallahatchie River, where it had lay for days, weighted

down by a 75-pound cotton-gin fan bound to Emmett's neck with barbed wire. His nose had been broken, his eyes plucked out and he

was shot through the head. Emmett had been kidnapped in the middle of the night from the home of his uncle, Moses Wright, on August 28th by Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam. Emmett was never seen alive again.

Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam were later found innocent of murder by an all-white jury, and were never tried for the kidnapping to which

they openly admitted. They later sold their murder confession to Look magazine for a few thousand dollars.

Justice was never done in the case of Emmett Till. Certainly not in the 1950s and not during the lifetime of Mrs. Till-Mobley

who worked tirelessly to help our society learn from Emmett’s story. But that soon may change. Filmmaker and activist

KEITH BEAUCHAMP has spent the last nine years completing his labor of love The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, a

documentary film that tells Emmett’s story in gripping detail through archival footage and interviews of living eyewitnesses

and family. But Mr. Beauchamp’s greatest triumph is the fact that after fifty years, the Emmett Till case has been re-opened

and the living people involved—but never charged—in Emmett’s murder may be indicted.

Mr. Beauchamp spoke with fRINGE magazine about his film and the Emmett Till case.

DEE DEE VEGA: I understand that your film, The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till has recently been released in cities across

the nation. What does this mean for the future of the project and for Emmett’s case?

KEITH BEAUCHAMP: On October 14th the film was released in seven cities across the country and it means a lot because it

isn’t just a film, it’s a movement, a breathing animal. The reason I say that is because the case is currently being

investigated. Right now, we’re expecting indictments to happen soon. We put the film in the theatres on the 50th anniversary

of Emmett’s murder—which is the reason Film Forum hosted the screening—because we wanted to commemorate the anniversary and

continue to keep the pressure on. The pressure that’s needed by the public to make sure that justice is done. My objective was always to bridge

the gap between the civil rights community and the hip hop community, to bring us all together under one banner fighting for

one cause. This cause is to help change the conditions we’re continuing to be met with throughout this country. I feel that

this film can be that tool to bring us all together.

DV: I see this film as a piece of activism rather than strictly functioning as cinema. How is that you came to make

a documentary rather than some other means of presenting Emmett’s story?

KB: I was first introduced to Emmett Till’s story at the age of ten when I was in my parent’s study and I came across the

Jet magazine photograph of Emmett and like many of us who saw that photograph for the first time, it shocked me tremendously. My

parents explained the story to me. But throughout my life, Emmett’s name kept surfacing. When I got to high school, I was

interracially dating. The last thing my parents would tell me when I left the house at night was 'don’t let what happened to

Emmett Till happen to you.' It was an education tool in my household to keep me aware that racism still existed in the Deep South.

Two weeks before my high school graduation, I had my own wake-up call. At a pre-graduation party I was beat up by an undercover

police officer for dancing with a white friend of mine. I want to do something to make sure that these things never happen again.

So I became part of the system in order to be part of the solution. I decided I wanted to study criminal justice to become a

civil rights attorney. During my junior year, some childhood friends moved to New York City and they had a film production

company. I came to New York and began working with them and I started writing and producing music videos at that point and I

ended up sitting out the rest of the semester—I didn’t finish school.

DV: It often happens like that!

KB: I had an opportunity to work on a feature. I was asked, 'if there were something you could produce, what would that be?'

And the first thing that popped in my mind was Emmett Till. So it started off as a feature film first. I was researching material

to develop into a screenplay. It didn’t become a documentary until I started finding eyewitnesses to the case, and Ms. Mobley

encouraged me to leave the feature film alone and do the documentary in order to get the case re-opened.

DV: I know you became very close to Mrs. Mobley. Can you describe that process?

KB: It’s a difficult question to answer because you know she passed away at the height of everything and it was a huge

blow for me. I was in a depression for close to a year, I couldn’t even look at the footage in the film. I was so agitated that

we had gotten this far and she saw everything happening before her eyes and she passed away without seeing the case re-opened. So

it was just heart wrenching to think about it because she’s one of the most influential people I will ever meet in my lifetime.

At the beginning stages of the project, I lost my grandmother and she filled that void. We were so close she called me her second

son. We used to sit on the phone and talk about what we were going to wear when we would go to court once the case was re-opened.

Those memories that I once shared with her…it’s very difficult for me to accept that she’s not here anymore. I haven’t had a

chance to properly mourn her passing because I’ve been working and trying to keep the promise that I made her before she passed

away, and that promise was to get the case re-opened—even if have to hold my film back to do it. I did that and I was able to

argue the case with the department of justice.

She was a very fascinating, intellectual woman. Very strong willed and very, very faithful because that’s how she was able to

get through those very dark chapters in her life, losing Emmett Till and fighting for 48 years to see that justice is done in his

case. For 48 years. So it was her faith that got her through this, and she nurtured me into the activist that I’ve become without

me even knowing. So she had a profound affect on my life and the makeup of the person I am today.

DV: I heard that there is a lot of footage you had to remove because of the re-opening of Emmett’s case. I know that there is probably a lot you can’t discuss, but is that footage going to be a part of another film?

KB: I am doing a second part to the film. It’s not a lot of footage. It’s just a lot of information on the case that people

know I have now that I removed from the film and that reason was because there is an investigation going on. I had to be smart

about it. It isn’t often where you have a film and a case going on at the same time. I never heard of anything else like that

happening before. I just want to be very careful because first and foremost I was here for Ms. Mobley and the witnesses who had

to live with this pain for fifty years. My objective was to get their story out there and give them a platform to speak

out—that was the first thing, being a filmmaker was second to me. Not too many people are able to tell a story that they

learned at the age of ten, to be able to contribute to the civil rights movement that still exists in this country.

DV: There’s a lot of historical footage in the film that is so moving such as the footage of Moses Wright. Was that

footage very difficult to access?

KB: I spent months just studying where this footage could possibly be. I was able to get the bulk of the stuff from CBS

and Fox Movietone, which was interesting because Fox was finding a lot of footage that was stored away and no one really knew

existed. They were just coming across these boxes of footage and I would spend all of this money just to transfer it so I could

look at it. There are still probably boxes that they’re finding now. I knew when we were finding all this footage it was going

to be expensive to use it in the film. But what was so interesting about the Emmett Till case is that it sparked the media

revolution in this country. That’s the only case that was completely documented by archival film, archive photographs and

microfilm. If you have those things, you can tell the full story of Emmett Till.

DV: I know that there were individuals such as Emmett’s cousins that appear in the film who had not been approached to

speak before. How did you go about persuading them to speak about Emmett on camera?

KB: That was really difficult because Simeon Wright, for instance—when I was spending a lot of time with Ms. Mobley, she

kept telling me I have to get Simeon Wright to talk. Simeon Wright was the cousin that was actually in the bed with Emmett when

he was abducted. For many years he didn’t want to speak out about this case because of what history has written about it, written

about his family’s involvement—they always blamed his family for the murder and kidnapping, so for so many years he just didn’t

talk. So Mrs. Mobley encouraged me to just continue to beg him to talk and finally after three years he came out and told me what

he knew about the case. When he told me, he introduced me to all the other eyewitnesses who were there on the night of the

abduction. They introduced me to other people and things began to snowball that way. But it took time to get the witnesses to

come forward and talk to me. I had to put the filmmaker’s hat aside and become friends with these people so they could trust me.

DV: Realistically, how many indictments could there be?

KB: I uncovered up to fourteen people involved with the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till. Five of these people were

black men who were employees of J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant. We believe they were forced to participate because they were employees.

Right now there are five people who I believe can be indicted.

DV: Your film clearly has expansive social value, but documentaries are made all the time. Who are some of the people who

helped you to bring this film to the public?

KB: THINK films came forward, which is a great thing because—black filmmaker and a documentary? (Laughs) It just don’t

happen! So THINK films believed in me and in the project. They had been watching me since I entered my film in the Hamptons

International Film Festival; they thought that I was causing a movement. This is a huge thing because films of this nature never

get picked up and normally these types of projects go straight to television. There has never been a film of this nature put in

the theatres. You have a lot of murder films that cover this stuff. You have films based on true stories—that’s one thing. Here

you have a documentary where you have the people themselves telling you the story of Emmett Till. You often wonder why films like

this don’t get picked up and put in theatres, but it’s because we don’t support them. I’m hoping and praying that people will

support this film because you aren’t just supporting me as a filmmaker, you’re supporting the case and you’re helping by showing

interest. The federal government will notice and Emmett’s name will be talked about all over the country. So my whole objective

from day one was to get the case re-opened, now I want to see justice done and get over this finish line that we’re coming close

to, and I need the support of the people.

DV: For people, especially young people, who see this film and become inspired—what are some things that they can do right now

to take social action?

KB: The best thing right now is to continue to go out and talk about Emmett Till. Ask teachers in school to talk about

Emmett Till. For our peers—you need to support the film. By doing this, you’re also supporting Hurricane Katrina. I’m from

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and have asked my distributors to work with me to help with relief. We decided to give a portion of the

national proceeds to Katrina victims. When the hurricane occurred, it happened to be on the anniversary of Emmett Till’s murder,

August 28th. I felt compelled to do something. But young people need to keep Emmett Till’s name on the forefront until justice

is done.

|